*Before we get into this, it’s worth noting that, unless you are already one of my subscribers, the odds of you seeing this post are very small. It’s the kind of post the Substack algorithm will want to hide because it interrogates Substack’s culture, structure and some of the platform’s practices. I’ve noticed the algorithm really pushes content that is highly complimentary towards Substack and far, far less of the opposite. So, if you get something out of this piece or feel it deserves a life outside of The Ampersand community echo chamber, please share it.

When I first joined Substack, I was filled with an overwhelming sense of possibility. I’d been lurking for months already, reading posts by other writers, and hitting the subscribe, follow, like and restack buttons with reckless abandon. Then, the Notes feature came along and it felt like Twitter but… kind. Supportive. Wholesome.

I decided I had to launch my own Substack. The allure of writing whatever I wanted and potentially getting paid for it was too strong for me to resist.

I spent months ruminating on what my newsletter might be like and, in the end, settled on the idea of “an interactive magazine for eclectic readers”. Culture, conversations, writing tips, creative prompts and, of course, personal and socio-political essays.

I’m a professional writer and have been grafting away in various different mediums for well over a decade now. Along with acting, it’s my bread and butter. So, while I’ve always felt excited by the prospect of writing for the joy of it, I was conscious of the fact that every essay I wrote here on Substack would take time away from my actual paid work. Writing on Substack would slow down the arrival of novel number three, my next stage play or a brand new TV pilot. & All that meant I had to earn at least a little bit of money to justify it.

But I knew I would. It may take a little time but it was going to happen. After all, I had proof. There were loads of great examples being paraded all over the platform. Emma Gannon and her 6-figure Substack salary. Cody Cook-Parrott making an impressive 5-figures a year. Leyla Kazim and her hundreds of paid subscribers and, really, I’d be here all day if I wrote a list of how many people seemed to be making good money through Substack.

With my industries (theatre, film and TV) still quivering away in the depths of financial hell, struggling to recover after a pandemic and two major strikes, the possibility of earning well via Substack felt like a little ray of hope.

I listened to countless podcasts, read dozens of articles and watched several round tables, all authored or led by people high up at Substack. They made it clear that you would be successful on Substack if you worked hard, posted regularly and were kind to your fellow Substackers. I knew I could count on myself to happily do all three of those things.

I reached out to the writer relationships team at Substack to ask for further advice on launching. I figured they might be interested in having people on the platform they knew would deliver quality writing and, as an award-winning TV writer with two books on the way, I thought they might consider me one of those people.

I was wrong.

The person I spoke to couldn’t have given less of a fuck. I wondered what working in the “writer relationships” department meant if they weren’t interested in fostering relationships with actual writers. Sure, none of us are entitled to anything but I thought Substack might appreciate my gumption and at least give me the time of day. Plus I’d seen other Substackers talk about how helpful people who worked for the platform were when they were starting out.

Eventually, I started to realise what it was that made Substack staff want to help those people and perhaps be less concerned with helping writers like me. It didn’t matter that I’d dedicated a huge chunk of my life to writing. I’m not famous, I don’t have proximity to fame and I didn’t have access to a huge following or mailing list I could bring with me. In short, Substack didn’t think I could make them money. &, So far, they have proved themselves to be absolutely right.

Nonetheless, the naïve newbie that I was ignored the curtness of the one-line reply I received from said Substack staffer. I thanked them for their time (all four seconds of it) and kept it moving. I’ve never had a leg up in any other part of my life and, in many ways, it feels all the more satisfying that I’ve earned everything I’ve got instead of being handed it on a plate. I’d simply have to do the same here, I decided.

I launched The Ampersand in May of last year and loved every minute of writing each and every piece. I began using the Notes function. I joined a couple of writing groups. I even started to make friends. It was like tumblr of old. Or Free Open Diary. Or Blogger. It just took up way more of my time. But it was worth it because, every now and then, I’d sit back, read one of my pieces and think, “Damn. I can really write an essay!”

Sure, I felt a little downhearted than no one actually seemed to be reading my essays, but, “build it and they will come”, I thought. Plus, I was having a great time and telling everyone who would listen all about this incredible platform. “You should join!” I’d tell them. “Everyone is so nice and you can actually get paid for your work!”

Being on the platform officially, joining certain groups and writing a few call outs on Notes for lesser known writers meant that my reading list grew and grew. I loved reading pieces from all parts of the world, from writers who had huge talent and were clearly putting the hours in. But soon I started to notice a worrying trend. There were writers of real quality who had been on the platform far longer than I had who were still struggling to get subscribers and interaction on their posts. These people had been shouting into the void for years. Was that going to be my fate too?

Meanwhile, I saw a growing number of celebrities join the platform. I wasn’t seeking them out. They just kept appearing. Their first ever Note, right at the top of my feed. Their smiling face looking up at me under “People to follow”.

It’s not that I’m totally disinterested in celebrities. Sure, some of them come here and make loads of money doing the absolute bare minimum and that’s kind of gross. But others are actually really good writers who post regularly and seriously care about their readers. My gripe, however, is this: What chance do the rest of us have if people who already have massive followings are being pushed so hard on this platform?

Then, I realised it: We little people are not meant to have a chance. We are just meant to think we have one.

It was when I was doing edits for my second novel that the penny dropped. False Idols is about a woman who accidentally falls into a cult after signing up for a movement and meditation class. The leader, Lilith, has a husband who our protagonist, Sadie, cannot stand and, one day, she finds herself down an internet rabbit hole researching the husband’s multi-million dollar multi-level marketing company. She scoffs at the idea of being part of a pyramid scheme and, of course, the irony is that she is trapped in a scheme just like it - she just doesn’t see it yet.

Reading my own writing back, it hit me: the irony wasn’t just on the page. I, too, was part of a pyramid scheme. I had been for months. The only reason why I hadn’t realised it before was because instead of financial investment, it was time I was investing. Hours and hours of free labour.

Otherwise, there were so many similar markers. The way I was always trying to recruit people. The fact I’d used the money I’d received from my own paid subscribers to subscribe to other Substackers who claimed to hold the secrets to how to make a living from Substack. The fact that so many of us with teeny, tiny followings talked about those with bigger subscriber lists like they were Substack gods. I began to question - Are we all here just to support the bigger names? Bums on seats to make this platform larger and spread the word?

Of course, Substack does a wonderful job of making sure its name is always front and centre when you talk about it. Tyler Denk wrote about this in his piece Death by a Thousand Substacks and quoted writer Anil Dash:

“Imagine the author of a book telling people to ‘read my Amazon’. A great director trying to promote their film by saying ‘click on my Max’. That’s how much they’ve pickled your brain when you refer to your own work and your own voice within the context of their walled garden.”

This quote got me thinking, because Anil is absolutely right - places that platform art don’t have the artists themselves speaking in this way. Social media platforms do. & You know who else? Pyramid schemes. There’s Tupperware parties, Avon Ladies… the list goes on.

Reading Tyler’s piece also got me thinking, as I so often do, about capitalism. One of the themes I explore in False Idols is how the wellness world has long since professed to be the cure for capitalism. Or, at least, a viable alternative. But the West’s commodification and cultural appropriation of Eastern practices has led to us all being sold watered down versions for a hefty price to merely cope with capitalism and, in so doing, continue to contribute to it.

Many of us like to believe that Substack is this utopian place that offers a true alternative to the capitalist monstrosities the likes of Meta, Twitter and TikTok have become. But the truth is, it’s still social media and, above all else, it’s still a business. A business that thrives on having people at the top and others at the bottom whilst giving us the impression it owns the means of production (the platform itself).

I was listening to this song by Joshua Idehen the other day and thinking about the socio-economic system Substack might fit into.

In the end, I settled on techno-feudalism.

As

writes in his recent piece Who Owns Substack, none of us quite know where this platform is going to end up, whatever the original intentions of its founders:“Every social media platform starts with a simple promise. Facebook wanted to connect college students. Twitter aimed to make status updates instant and conversational. Instagram focused on sharing beautiful photos. YouTube made it easier to upload and share videos. TikTok encouraged creative expression through short-form clips.

At first, these were just ideas—small, scrappy ventures built by idealistic founders who claimed to care about users, creativity, and connection. The platforms weren’t polished, they weren’t profit-driven, and in many cases, they weren’t even sure what they would become.

But then, it happened. The tipping point.

Once a platform hits a critical mass of users, everything changes.”

I can’t remember the exact moment Twitter became full of hate-spewing trolls. I joined so long ago (back in 2009) that I can’t actually remember if it was ever a nice or even half decent place. But there must be a reason I stuck it out long enough to become entrenched enough to not want to leave. Even when the trolls started spewing hate in my direction. &, Thanks to Elon Musk’s takeover of the social platform, it truly has become anything but social. There really aren’t many, if any, redeeming qualities at all.

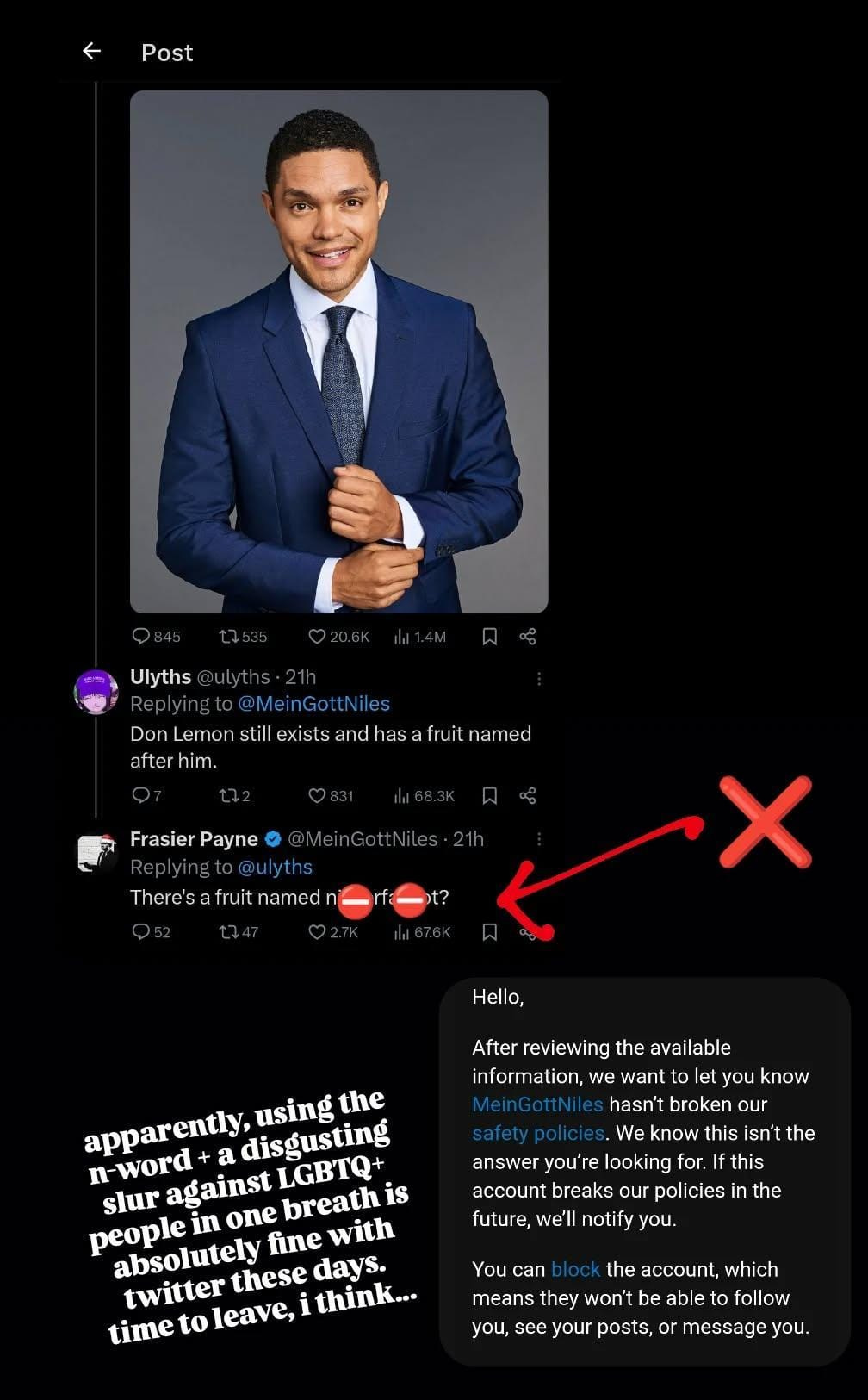

I recently reported a user for referring to former Daily Show host Trevor Noah as an n-word. I filed it under “discrimination” and “hateful slurs” and was later emailed and told that the user was not in violation of Twitter’s “safety policies”.

So, of course, I want to believe that Substack is a haven from this kind of behaviour. But, recently, I’ve read more and more pieces on and off Substack about why many people have decided to leave in the last year. TERFism, racism, homophobia - there’s lots of it here and, like Twitter, Substack won't do anything about it because, exactly like Elon Musk, they believe in “free speech” even if it encroaches on the rights of others.

Apparently, Substack uses the algorithm to sequester right wing and left wing users, which is why you might be reading this piece right now thinking, “I haven’t seen any nastiness here”. However, the algorithm doesn’t always work and when disgusting comments (particularly on Notes) slip through the net, whether you report them or not makes no difference. Substack will not deplatform users. Even if they are Nazis. Or at least, not just because they are Nazis. There needs to be clear “incitements to violence”.

Substack claims the reason they don’t want to deplatform users with controversial views is because they believe in “robust debate” which perhaps, on the surface, sounds rather reasonable and somewhat noble. But when you consider the fact that Substack takes a 10% cut from all paid subscriptions, including those received by these far-right accounts, it makes their intentions seem a lot less virtuous.

It all comes back to the same thing: Substack is a business. & Unfortunately, it’s a business that profits from white supremacist content.

Meanwhile, the majority of African writers on the platform are unable to monetise their writing at all due to Substack’s insistence on using Stripe and Stripe alone for subscriptions. You guessed it… Stripe isn’t available in most African countries.

As

says in their piece on the subject:“This is where it all starts to feel like modern-day slave labor. These platforms expect us to create, innovate, and keep them relevant globally, yet they systematically exclude us from their reward systems. How do you claim to be about sustainability and equity while shutting out an entire continent?

Here’s a disclaimer before Substack bans me: this isn’t an attack; it’s the reality. Creatives across Africa are building these platforms with their contributions, but the return is crumbs.”

Whilst I was researching these issues, reading the thoughts of departing Substack writers and those of journalists, I read this article in The Atlantic and accidentally stumbled across a surprising piece of information. Something that clarified and perhaps, intensified, my first concern about celebrity Substackers and their preferential treatment by the platform.

The article states that “from the beginning”, Substack has “actively courted big-name writers” and has “offered them advances, as a publishing house might”. As someone who recently went through the process of getting an audiobook out into the world and someone who is soon to make a print publishing debut, I know that advances, large or small, are always given with the idea that the publishing house who doles them out will make that money back (and then some). The promotional campaign around the book in question often reflects this. It’s how the publishers ensure their rate of return.

All this made me wonder: Just how many big names, some of whom aren’t necessarily known for writing, have been invited onto this platform and offered cash incentives before being pushed relentlessly in our faces so that Substack makes its money back?

So, what can we do about it?

Leave

Remember the afore mentioned Cody Cook-Parrott? Well, despite their 5-figure yearly Substack salary, they recently left the platform for reasons I do not know and are now helping others do the same through 1-2-1 advisory sessions.

Here, also, is a great piece in which critic Ty Burr details his experience of leaving and offers advice to those considering it themselves.

If you do leave, don’t be afraid to say why. My hope is that, the more people speak out, the more pressure Substack will be under to do better.

But what if you’re not ready to leave yet?

I know I’m not. At this point in time, the good is still outweighing the bad. Also, I’ve experienced far-right extremism on pretty much every platform I’ve ever been on and it’s hard for me to believe that any platform, no matter how well it starts out, won’t end up corrupted in the same way. Because… well… capitalism.

Stay here but take your money elsewhere

You know that option in your navigation bar that allows you to pick a button? There’s an option in the drop down that lets you customise one and that button can link your readers anywhere you like. Fourthwall. Buy Me a Coffee. Ko-fi. Patreon. Paypal. Your website. Whatever you choose.

It took me about 5 minutes to set up this Ko-fi account and means that people who aren’t ready to commit to a paid subscription but still want to support my work or say thank you for a specific piece can do so very easily.

Find community here and give it life outside of Substack

The community groups on Substack are one of the best things about being here. So embrace them. Fully. Join the online group writing sessions. Stick around to bitch, moan, rejoice and celebrate each other in the breakout rooms afterwards. & Then, take those relationships offline.

I voice note one of my friends here on Substack fairly regularly. That same friend recently took a six hour flight to visit someone else they met on Substack and had the best time ever.

I really believe these genuine, human relationships are how we make Substack work for us.

Safeguard your time and energy

Part of the bitterness towards this platform comes from a place of feeling as if you are doing hours and hours of free labour for nothing but pennies in return. If you feel this way, it’s time to consider how you can do less and make sure you’re truly enjoying the writing itself, not just churning out content for the sake of it.

Your subscribers are subscribed to so many other things, they may not even notice if you don’t post that week.

Personally, I’m going to be doing some posts that are part writing, part voice notes and experimenting with shorter posts too.

Think about what you can share that’s already written. & How about re-publishing posts from a long time ago that didn’t get much love back then but certainly deserved it? Your subscriber list has likely changed since then and many of your readers might appreciate you sharing something they missed because they weren’t subscribers when you first published it.

Safeguard your data

Go to your settings and download your data. Ideally, every time you post something new. This is how you make sure you own all of your pieces and your subscriber list and can take it all elsewhere no matter what happens on/to Substack. (Thanks to

for teaching me this one!)Switch off AI training

Did you know that, unless you opt out, Substack automatically uses your writing to help train AI? Yep. I was horrified to recently learn this too. Go to your settings and switch that bitch right off.

Make hay while the sun shines

Substack may not be here forever and, even if it is, it’s possible this is the best it will ever be. We’ve already seen the encroachment of new features that many of you do not like and, as William said in his piece, greed and corruption will likely, eventually, take hold. So grow here while you can and while you still enjoy it. Connect with as many people as possible. & Don’t be afraid to ask people to pay for your work. One day, you may want to leave and, when you do, you’ll want to take as much of what you worked for here with you as possible.

Don’t spend too much time here

In the immortal words of Prince…

I’ll say it again: Substack is social media. Which means you are both the consumer and the product. So, treat it as you would any other social media and don’t spend too much time here.

Real life is out there.

Go enjoy it.

Now.

With love,

xK

Clicking the like button on this post means more people will see my work. But, if you really love it, why not share it?

Great piece Karla and some good ideas (as well as food for thought) about how to use this space so it works for us.

Really interesting food for thought, thank you