It’s been a whole two weeks since I last posted on Substack - my longest break from the platform since I joined in mid-May. I spent most of that time on holiday in Italy (a wedding in the south and then up to the mountains for some quality time with friends). Unfortunately, I got a nasty cold while I was away and spent the final few days recovering. Annoying as it was to get lumbered with a virus during my first proper break since April, I do think it may have been my body’s way of telling me to slow down for a bit.

It’s rare that I get sick and don’t attempt to just power through but, this time, I spent the best part of two days in bed. I slept, watched ER re-runs and took time to reflect. Being ill on vacation obviously isn’t the most ideal scenario but having the space to pause was actually really valuable.

With a big deadline looming, I had to jump into edits for my second novel as soon as we landed back in the UK and, just over 24 hours after we got off the plane, I was on a train down to London for a visit I’d planned weeks in advance. On the journey, I pictured myself attempting to manage all of this whilst still struggling with illness and I don’t doubt that would’ve been the consequences of me refusing to rest back in Italy.

I’d done the right thing. Whilst lying in bed might not have been how I’d planned to recharge whilst on vacation, it was clearly what my body needed.

Intentional rest is a gift. A gift that, in the end, afforded me the opportunity to enjoy every part of my trip to London - most notably, my visit to the Tate Modern, where I finally got to see The Expressionists exhibition.

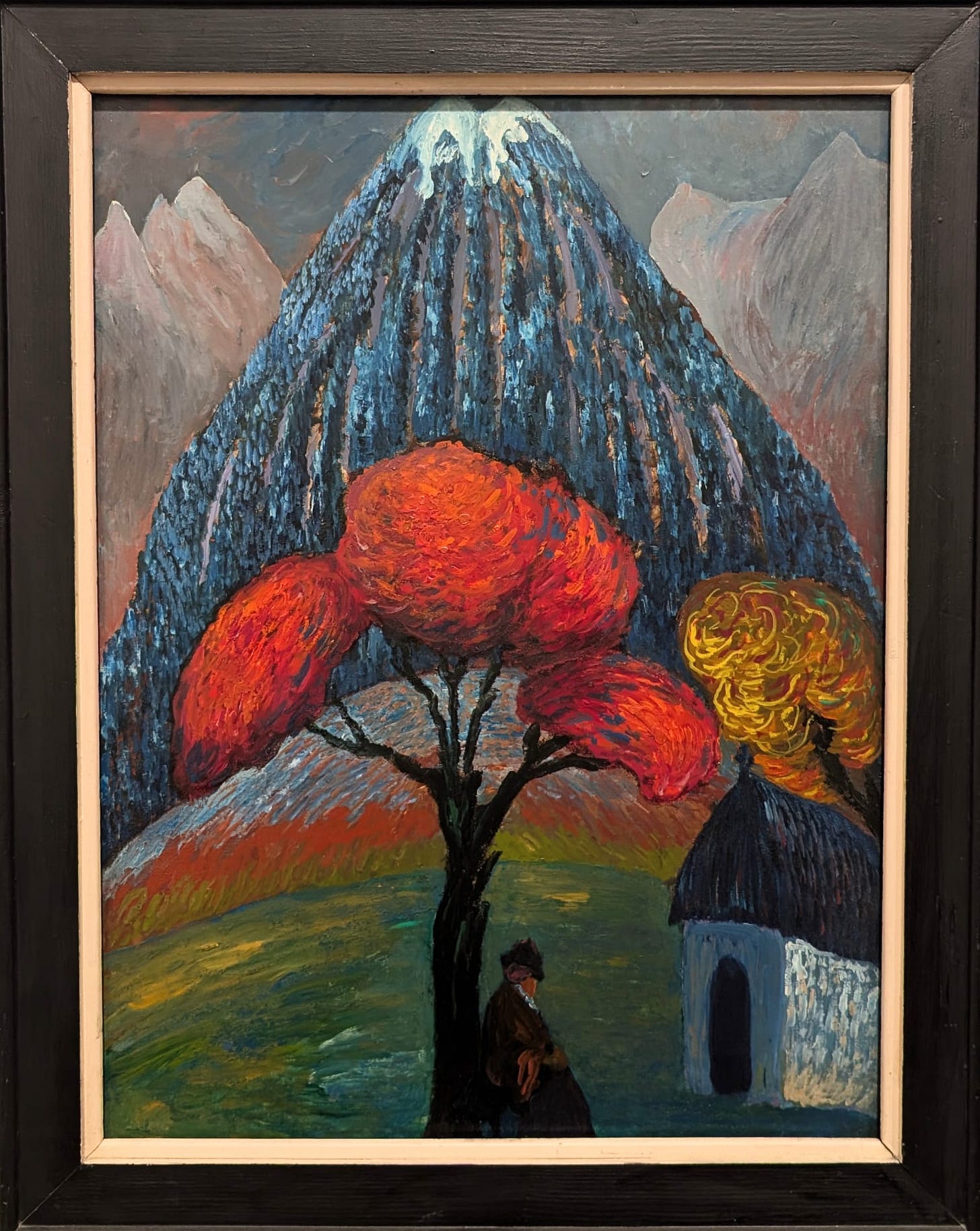

For as long as I can remember, I’ve been a huge fan of Expressionism. The vivid colours, the sense of movement and life, the varied subject matter. Expressionism is to visual art what Jazz is to music. It is the soul releasing itself onto the canvas. Playful, emotional, full of intricate beauty but rarely pretentious.

Wassily Kandinksy is arguably the most famous member of this movement and certainly one of my favourite artists of all time. Franz Marc is a close second. What I didn’t know was that both these men had partners who were phenomenal artists in their own right but whose talent is seldom exalted to the same degree thanks to - you guessed it - the patriarchy.

The Tate Modern’s six month exhibition sought to change that, showcasing the work of Gabriele Münter, Maria Marc (née Franck), Marianne von Werefkin, Elisabeth Epstein and Erma Bossi - friends, lovers and wives of the male artists we already know so well. It was refreshing to see their work displayed, at long last, alongside Kandinsky’s lively abstracts, Jawlensky’s sumptuous portraits and Marc’s glorious animals, often seen through prisms of light.

Werefkin and Jawlensky were lovers for 27 years and she trained him to become the exceptional artist we know him to be. Five years his senior, she was far more skilled than he when they met and she worried he would become jealous if she didn’t help him realise his full potential. She also confessed, in her writing, to hiding her art from him and of her hopes that he would be able to achieve the type of artistic success women were denied.

It’s a tale as old as time. Even the most basic art enthusiasts know the tragic story of Camille Claudel - extraordinary sculptor and “mistress” to the better known Auguste Rodin, who was 24 years her senior (!). It’s fair to say that Camille was a genius and yet, thanks to lack of funding for female artists, she was forced to rely upon Rodin financially or collaborate with him. He, of course, took the credit for their collaborations and never fully committed to her. Because of this, and her own family effectively cutting her off, she lived in relative poverty.

Ten years after meeting Rodin, he had ostensibly abandoned her for another woman but Camille had been offered an incredible opportunity: a government commission. She created a piece called The Mature Age which was an allegory for ageing and featured a figure leaving youth behind and progressing towards death. It could also be interpreted as Claudel pleading with Rodin to return to her and, when the latter saw her work in progress, he was enraged. It’s possible he had something to do with the commission being cancelled and few people seeing it in Claudel’s lifetime.

Years later, she accused Rodin of stealing her ideas and attempting to kill her. Based on all he’d put her through in the time that he’d known her (a highly toxic relationship, an abortion, refusing to commit etc), I think it’s possible these allegations were entirely true. Unfortunately though, they lead to her spending the last 30 years of her life in a mental asylum, despite doctors begging her family to allow her to live freely.

This is how female artists were treated during the late 1800s and early 1900s, which is also the period our Expressionists lived in. So, it’s no surprise these women existed in relative obscurity. Münter, whose extensive work felt like the backbone of the Tate’s exhibition, was a prolific photographer and writer who spoke multiple languages and travelled the world, documenting much of what she saw. Not nearly enough people have heard of her. But perhaps being afforded the opportunity to create without being committed to an institution means that she was one of the lucky ones.

How hard it must’ve been to tread such a dangerous line though. Knowing that the viability of your artistic life might depend so heavily on whether a man still finds you attractive or not. The idea that you may even need to hide your talent or feed them your best skills for fear they may otherwise grow jealous and cast you out. I wonder if these Munich-based women artists knew of their contemporary Camille Claudel. I wonder if they talked about her in smoky bars or coffee shops and advised one another on how to avoid a similar fate.

It’s possible it all came down to class and capital in the end. Werefkin was born into Russian nobility, had generational wealth to fall back on and was gifted a large studio on her family estate. Münter grew up in an upper middle class family who supported her and gifted her a private tutor.

I wish I could say the opportunity to make art everyday was no longer so dependent on coming from a wealthy background. However, the state of arts funding in the UK and US, as well as the prevalence of nepo babies, spouses and siblings, means having access to privilege still seems to be the key to artistic survival - and certainly to making it big. I feel like cheering every time I see someone from a low income background cut through to the mainstream. But it doesn’t happen nearly enough and most of those that “make it” seem to be men.

Despite their privilege though, the women of the the Blue Rider movement still struggled to be seen and this is absolutely indicative of the rampant sexism of their time. For me, getting to see their work in person was both inspiring and educational. These women never shied away from making statements about gender and its potential fluidity and captured their unique perspective of the world in living colour. If you couldn’t make it tothe exhibition, I strongly recommend you check out their work online.

I thought of the women of the Expressionist movement many times after going to see body-horror flick The Substance at the cinema. The film sees Hollywood starlet Elisabeth Sparkle (played by Demi Moore) accept a Faustian Pact in the hope of returning to the youth she feels she has lost.

It’s essentially a modern take on The Picture of Dorian Gray and serves as a satirical takedown of the unattainable standards of beauty women in the public eye (and, as a whole) are expected to not only achieve but maintain. Elisabeth makes some wild decisions, admittedly, but her desperation is palpable, heartbreaking and, unfortunately, understandable.

The film explores the fetishisation of youth and the dehumanisation of the elderly, despite (or maybe because of) the fact that we know we will one day be old too. If only reaching “the mature age” wasn’t so terrifying.

I loved the theme of the fractured self and how, as humans, we so often forget that we have multitudes within us. Hating and beating up on one part of ourselves will be detrimental to who we are as a whole. Just as not being mindful of our future selves will almost always lead to irreversible damage.

The film also drives home the point that the people who are consistently making the big decisions about women’s bodies, our place in the home, workplace and society, are men. Often quite disgusting men whose priorities are only ever themselves and the capitalist system they thrive within. This is exemplified in a particularly stomach-churning scene in which TV producer Harvey (played by Dennis Quaid) messily consumes a prawn cocktail whilst telling Elisabeth that no one wants to see women over 50 on screen. The irony is far from subtle.

The idea that the patriarchy would like women to disappear the moment they are no longer convenient to men is as dreadful as it is true. It explains what happened to Camille Claudel and is why the women of the Expressionist movement were forced to operate within certain boundaries. It’s unsurprising that The Substance was written and directed by a woman. It isn’t horror for the sake of it. It’s a cry for help, a shot across the bow, a film that’s asking us, as a society, to do a hell of a lot better.

With love,

xK

Don’t forget: the simple act of clicking the heart button at the bottom of this post means more readers will see my work. I’m also never happier than when I’m reading your thoughts in the comment section. See you there.

Previous issues of Cultural Exchange that you might enjoy:

Great piece, Karla ❤️

Thank you. Insightful ❤️